The Face of Detachment

For a long time, I've been fascinated by the artistic union between writer Kobo Abe, director Hiroshi Teshigahara and – by extension – cinematographer Hiroshi Segawa. After reading and watching their most acclaimed works, The Woman in the Dunes and The Face of Another, I came to see them as undeniable masters of themes like social alienation, emotional detachment, and the conflict between the individual and the collective. Their stories' moral dilemmas and psychological tension were burned into my memory, enriched by their striking visual style. To better organize my thoughts, reflect on these recurring ideas, and celebrate the aesthetic of these works, I decided to write a series of short essays on all of their collaborations, which I present below.

Pitfall

Pitfall is the first collaboration between Hiroshi Teshigahara and Kobo Abe. Released in 1962 and based on Abe's television play Purgatory, it doesn't so much tell a story as it constructs a puzzle, assembled from disjointed narrative pieces. Viewed from a distance, the whole canvas suggests a somewhat cohesive tale about a mining worker who becomes an innocent, random victim of a corporate conspiracy. But the film's structure is more like a self-referential patchwork, with each segment drawn from vastly different narrative threads – some overt, others subtle.

One of the more apparent threads is the film's political message. Created in the early 1960s by pacifist artists shaped by the horrors of WWII and Empire's army, it's no surprise the film leans toward a leftist critique of contemporary society, especially on Abe's part, given his post-war membership in the Japan Communist Party. The struggle of the working class to unionize and resist the brutal exploitation of their labor (and, ultimately, their lives) is a theme found in art across the world at that time. Teshigahara's experience as a documentary director is evident in brief but striking images of real mining catastrophes, lending credibility to his description of Pitfall as a "fantasy documentary".

Continuing the thread of social anxiety, a subtler theme emerges: society's trauma forced by militarization. The line between citizen and soldier is blurred, and military elements seep into everyday life. There's no explicit indication of when the film is set, but it seems to take place a few years after the Empire's defeat. Yet, mining workers who flee inhumane conditions are referred to as "deserters" and are hunted down by the government to be either returned or punished. The term "deserter" struck me so strongly that I initially interpreted it literally. Only as the story progressed, especially when union themes emerged, did I realize it was metaphorical. Still, it doesn't feel like a careless slip of the tongue. Military motifs creep steadily into the narrative, such as an army propaganda poster casually displayed near a cashier's window. Later, that same cashier picks a "deserter" out of a line, checks his identity, hands him instructions and a paper with a map – a scene I couldn't help but interpret as a symbolic delivery of a draft notice and military orders.

Another compelling dynamic plays out between a man and his son. There's no mention of a mother, not even in passing, and I kept wondering whether "son" referred to a literal relationship or was simply a way for an older man to address a younger boy. The contrast between their personalities is stark and shows in nearly every scene. The father is talkative and easily connects with others. The son is withdrawn. Apart from a few screams in the ghost town, I don't recall him making a sound throughout the film. The father, though rebellious enough to escape the mine, generally follows rules and obeys authority. This is evident in the scene where his new employer makes him jump repeatedly, laughing at him. The boy is more "street-smart", unafraid to steal (even from the dead) and quick to hide when danger is near. The man is a dreamer, full of compassion and emotion, while the boy turns out to be capable of sudden, almost sadistic killing of a frog and stays unemotional when his father is killed before his eyes. He only sheds a tear when his father is killed a second time – or at least when his doppelganger is.

The doppelganger motif is a well-known narrative device used to represent internal division – opposing tendencies or ambitions within the same person – and often underscores the dream logic of a story. I interpreted this subplot as an extended dream sequence beginning the night before the escape. The man jokes with his friend, asking what he'd like to be in the next life. Answering for himself, he says he wants to work somewhere where unions exists and kick his boss's ass. His friend, perhaps half-seriously, says he'd like to be reborn as a demon. Later, the man, consumed by thoughts of real-life horrors and dreams of a better future, wanders into a ghost town. It's populated by phantoms who ignore him and by a woman (perhaps a flawed mother figure) selling rotten candy and waiting for a letter from her loved one. Eventually, the man becomes a union boss – clean, dressed in a white shirt – who beats his former comrade, another union boss with physical deformities, dressed in gray clothes that recall his own miner's past. Hisashi Igawa plays both roles brilliantly as two sides of the same coin. Both versions share empathy and communicability, but while the miner follows orders and respects authority, the union leader makes bold decisions and earns the boy's respect. Yet, like many dreams, the story ends without satisfying closure. Both men die in the same spot, in the same position, by the same weapon – making the entire fantasy a closed loop of self-fulfilling prophecy.

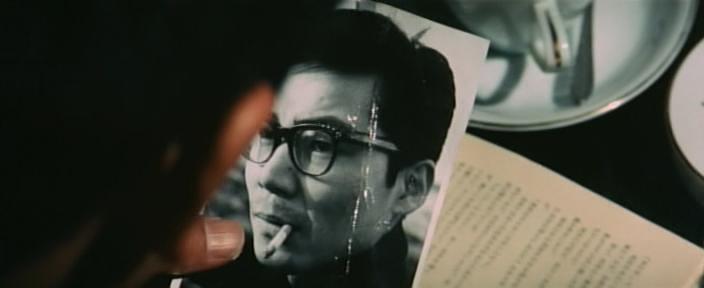

And speaking of a prophet, Pitfall has one character that fully fits this role. Man in White, the omnipotent uncanny figure played by Kunie Tanaka, perfectly summed up in his final line – "Exactly as planned". Everything about him signals an otherworldly presence. He's a film noir character dropped into a genre-bending story, bringing elements of elegant brutality and mysterious high-tech espionage. He wears a bright white suit but isn't afraid to literally step into the mud and do dirty work. He seemingly has endless financial resources – standing in stark contrast to the abject poverty around him – the motif that evokes the mine owner seen early in the film, also dressed in white and on the verge of becoming very rich. He first appears behind tombstones in a graveyard, photographing a man whose image will later be used to identify him for metaphorical military conscription. Every time he appears, it's as if from nowhere, and each time he vanishes into some otherworldly place. Even the cop runs away in terror upon hearing his motorcycle, as if seeing a ghost. Everyone who sees the Man in White eventually dies – except for the boy, who, it seems, is invisible to him.

It's difficult to untangle all the allusions that Abe and Teshigahara pack into just 97 minutes. The densely layered philosophical themes and elusive parallels can be a creative trap for inexperienced artists, who often lack the command of the medium needed to balance complexity and clarity. And yet, Pitfall is an extraordinary accomplishment for both creators. Rather than collapsing into incoherence, they succeed in crafting a haunting, existential puzzle.

Woman in Dunes

The Woman in the Dunes by Kobo Abe was published in 1962, followed by a film adaptation directed by Hiroshi Teshigahara in 1964. The screenplay, adapted by Abe himself, remains very close to the original novel. Both works were critically acclaimed upon release and have stood the test of time, rightfully earning their place as classics of world literature and cinema.

The story follows a young schoolteacher from Tokyo who spends his free time studying insects. While on vacation, he travels to a remote village located in a desert near the seashore in search of rare specimens. Losing track of time, he misses the last bus back and accepts the villagers' invitation to spend the night in one of their homes. He is sent to stay with a young widow whose house is located at the bottom of a sand pit. The next morning, he discovers that the rope ladder – the only way in or out of the pit – is gone. It is soon revealed that the man is to be kept there as a laborer, helping the woman dig sand, which the villagers illegally sell to sustain their livelihoods – at the cost of what is essentially slave labor.

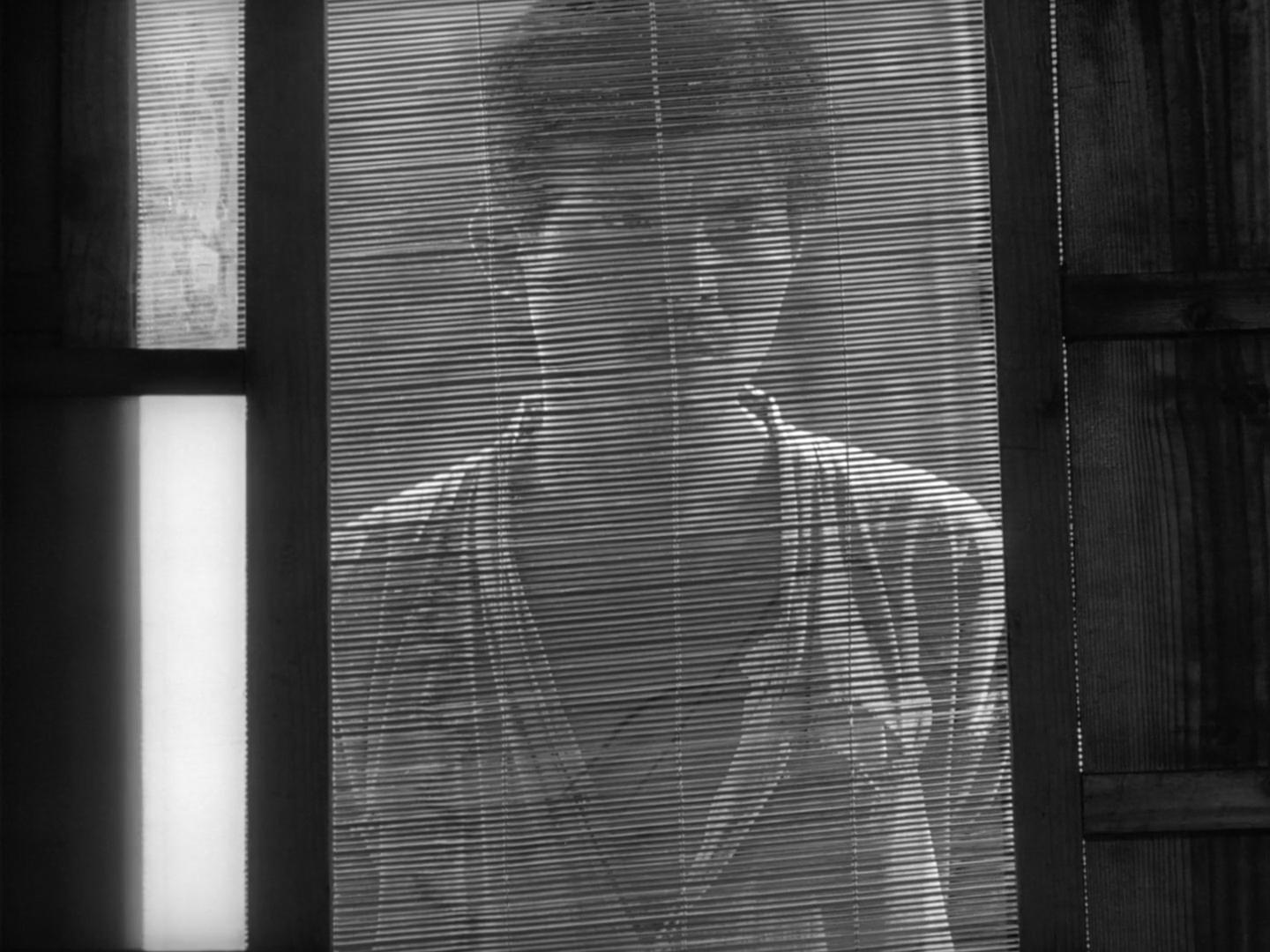

Created with the direct involvement of the novel's author, Teshigahara's power as a director shines not through the plot itself, but through the visual language and cinematic details with which he enriches the story. The minimalist set design highlights the woman's ascetic lifestyle and emphasizes the bleak, repetitive nature of her existence. Almost the entire film takes place inside a single sand pit, giving it a stage-like intimacy that reflects Abe's background as a playwright. While the pit already feels claustrophobic in the book, the film makes you truly fear it. One of Teshigahara's most remarkable achievements is his ability to convey the complete impossibility of escaping the pit without outside help – something that can be difficult for urban readers to fully imagine when reading the novel.

Yet of course, the set serves only as the backdrop for the human drama to unfold, and this is where the characters truly come to life. It is undoubtable that the story is filled with whole pack of allegories, be that social, political or philosophical. But one particular reading was speaking louder to me amongst the others, which can roughly be outlined as a question of life and time preferences.

The man, played by Eiji Okada, comes from a big city, but he deliberately chooses to somewhat alienate himself from society by focusing on teaching children and studying wildlife. Society's high standards and demands are reflected in his dream of being recognized as the author of a biology guide. This underlines his struggle with living not in the present, but in the future. It is symbolized by his desire to be remembered, because by his own words the only thing that matters is to leave behind something that lasts.

His attitude toward the world around him is filtered through logic and scientific knowledge. Although he has voluntarily distanced himself from modern society, he is still influenced by its conventions. When listening to the woman's story and becoming aware of her troubles, he says all the "right" words of sympathy. Yet he remains emotionally detached and does not connect her suffering to his own life. Even after he is placed in the same situation as the woman, he continues to cling to rationality and common sense. Throughout the story, he insists that someone will find his open books, deduce where he went, and eventually rescue him – bringing justice to his captors. But these threats come across as bluff, and even he is uncertain whether society cares enough to search for him. As the hope of escape fades, this belief becomes a comforting lie, something he repeats to save himself from falling into despair.

In the end, the only way society acknowledges his existence is through a cold and brutally brief court statement declaring him legally dead seven years after his disappearance. This moment is depicted slightly differently in the book and the film, but taken together, they paint a clearer picture: the man was around 30 years old at the time of his abduction, and the missing person report was filed by his mother. The woman he had been living with – the person supposed to be closest to him – could only say that he had gone to collect insect specimens. The police assumed he had run off with some woman, while his colleagues speculated that he had committed suicide, dismissing his interest in insects as a useless hobby and even a sign of psychological instability.

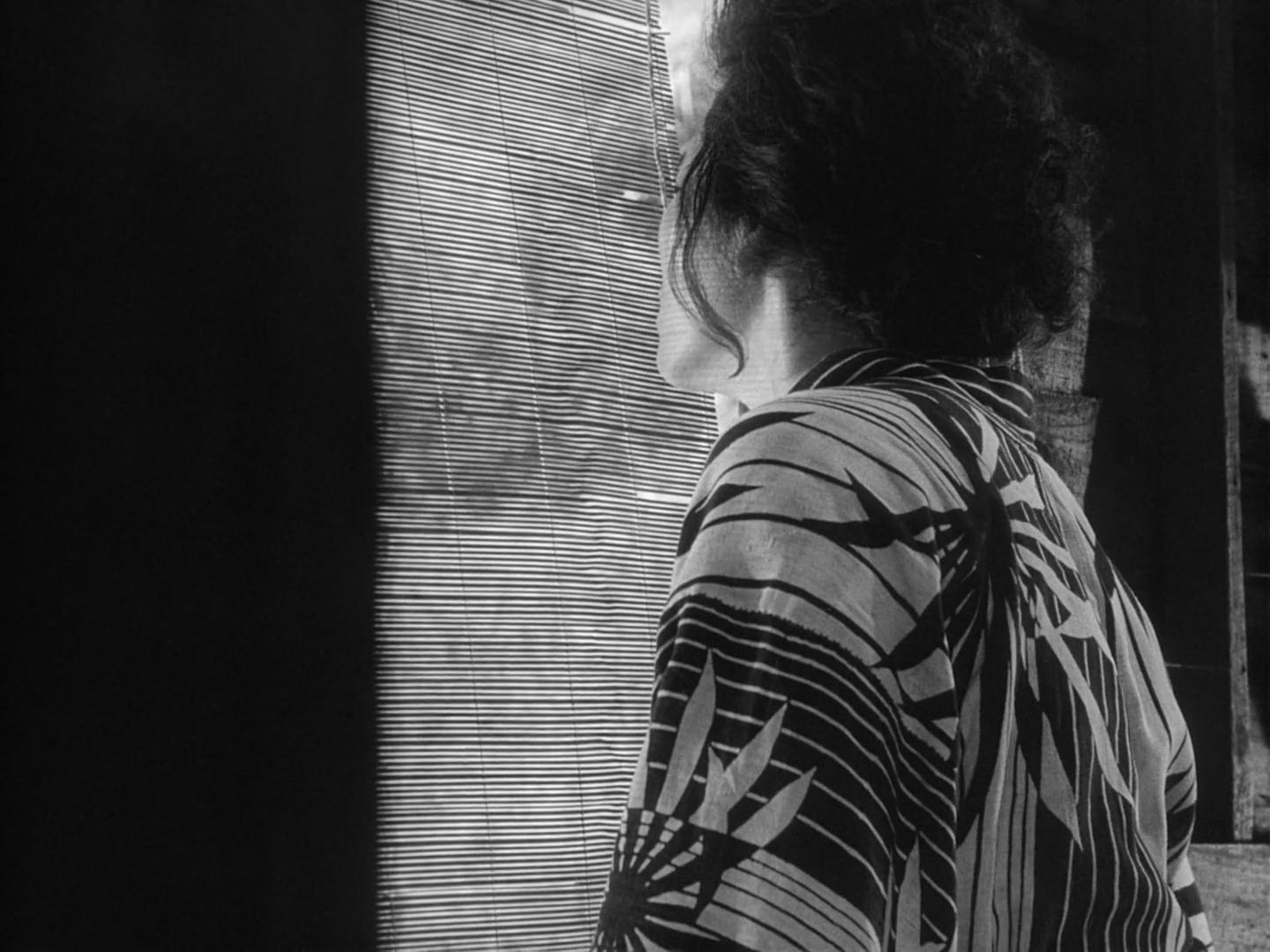

The woman portrayed by Kyoko Kishida. Her daily life is a sharp contrast to the man's. She belongs to a closed, vanishing community of only a few dozen people. Her existence revolves around the daily struggle to keep the sand away. Making long-term plans sounds so absurd that she doesn't even seem to consider it. The Sisyphean labor she endures is her past, present, and future – consuming her memories, thoughts, and hopes.

Being suppressed by the other villagers, she has learned not to complain and to wear a kind of emotional mask, hiding her fears and insecurities. Even discussing a tragic death of her husband and daughter seemingly doesn't reflect on her mood more than a slight change of a tone. She is afraid of the outside world and does not seek a way into it. Yet she remains intrigued by its inner life – wishing for a radio to hear the news and wondering if she is as beautiful as women in the city.

Her actions are dictated by practicality, forced by her environment, rather than by internal deliberation or logic. She knows how to deal with problems within her small, dunes-bound world – whether it's cleaning dishes without water or finding scattered beads in a pile of sand. The absurdity of her labor and the villagers' abuse don't seem to visibly bother her. Instead, she chooses to ignore it consciously. This is made disturbingly clear in the scene where the neighbors try to force the man to have sex with her in public. Although she acknowledges the injustice, she refuses to change her behavior afterward.

The way two main characters are portrayed highlights a fundamental tension between two opposing approaches to life: striving endlessly toward a future ideal at the expense of the present, and becoming consumed by the demands of daily tasks, finding a comfort zone even in harsh conditions, with little thought for what lies ahead. A lack of balance between the two causes them to miss out on life in different ways. A person's life shouldn't be measured in binary terms – successful or not – as if its worth were reduced to points in a video game. At the same time, a human life must not resemble that of an insect, driven by repetition, survival, and instinct alone.

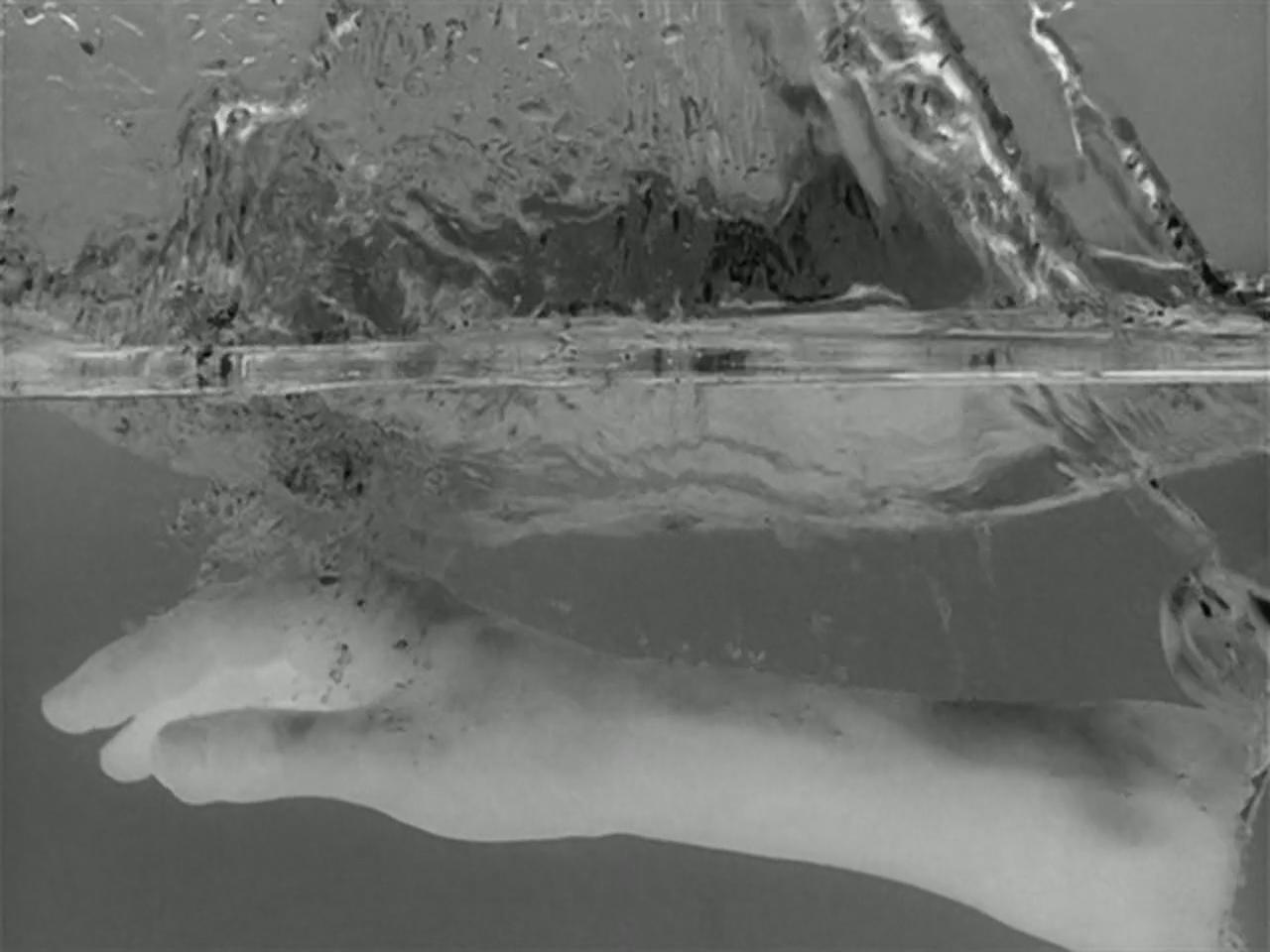

The third leading character visually embodying this dichotomy is the sand itself. The metaphor of sand as time is an ancient one, and when used carelessly, it can feel heavy-handed or cliched. Fortunately, Hiroshi Segawa's cinematography is as striking and nuanced as one could hope for. His lens moves effortlessly from the dead stillness of eternal dunes to the ceaseless motion of shifting sand, giving the sand a presence of its own – a silent, omnipresent force that barely responds to the actions of the human figures. By focusing largely on close-ups, Segawa draws a clear parallel between the man's view of living insects as mere objects, and time's similarly indifferent view of humanity as unremarkable. The black-and-white film and beautiful frames' fade-aways both heightens this effect, turning the pale sand into an endless, luminous canvas across which the dark, greasy silhouettes of people struggle and vanish.

This is a truly monumental work of art, both technically and artistically, offering space for deep reflection on profound and often troubling questions.

White Morning

White Morning, also known as Ako, is a 1964 short film directed by Hiroshi Teshigahara and written by Kobo Abe, based on his own short story. It was released as part of the anthology La fleur de l’âge, ou Les adolescentes, which focuses on the lives of teenage girls. The film depicts a single day in the life of 16-year-old Ako, played by Miki Irie, who lives in a kind of dormitory with other girls. They all work at a bakery, and on a day off they join a company of boys from a car wash to visit an amusement park and go for a ride together.

Despite the anthology's French title and Teshigahara's clear admiration for the French New Wave, the short is unmistakably influenced by American culture. After bowling and passing by an English-titled shooting gallery, the teenagers hop into a Pontiac driven by a rockabilly-styled boy and embark on an aimless trip – effectively transforming the short into a road movie with scenes that could easily have appeared in a 1950s American film. The opening credits, which explicitly state Ako's age and Japanese nationality, seem deliberately chosen to contrast this foreign, carefree lifestyle with the harsh reality of her everyday existence: monotonous labor in a bakery surrounded by bleak industrial settings and machinery. Like the world around her, Ako has her conflicting sides – she might stay silent while the others laugh, send mixed signals to the boy who likes her, and encounter anxieties of her own.

The film is beautifully shot by Yasuhiro Ishimoto. The black-and-white cinematography offers stunning contrast and clarity, drawing the viewer's attention to precisely the right details. Both the actors' emotional close-ups and the sparse industrial landscapes are visually stunning. By allowing the camera to become an active participant among the crowd of teenagers, Teshigahara and Ishimoto step into the territory of Direct Cinema, lending a greater sense of intimacy to the characters' perspectives. Teshigahara's trademark surreal fade-ins and layered images are also present, transforming even a simple loaf of bread into something mysterious and almost ominous.

Face of Another

Published in 1964, The Face of Another was followed by a film adaptation in 1966. Unlike the earlier The Woman in the Dunes, at first glance, the narrative structure here appears significantly altered.

The book is composed of a series of letters written by the main character, Mr. Okuyama, to his wife. These are in the first person, chronicling his life after a work-related industrial accident disfigures his face. In a state of understandable emotional distress, he fills the pages with reflections on the nature of human faces: what it means to have one, how society and individuals perceive facial expressions, and the significance of identity tied to appearance. He debates himself, wrestling with elevated philosophical questions alongside practical concerns. One such concern leads him to an engineering solution – constructing a human-like mask to restore a resemblance of normal life. Okuyama devises an elaborate production plan and ultimately succeeds in creating the mask. Yet, this achievement ends up with a dissociative crisis, as he begins to wonder whether the mask makes him a new person, and where new possibilities might lead him. In the end, he confesses to his wife that he seduced her while wearing the mask – causing her to cheat on her husband with her husband, now disguised as the Mask.

Given that the novel is written in a first-person narrative, an obvious and straightforward approach to a film adaptation would be to use an off-screen monologue for the main character. This would be a safe choice – and even if a less talented director had taken on the project, it could have resulted in a competent film. But by choosing not to follow this route and instead attempting something unique and daring, I think Hiroshi Teshigahara proves himself to be a true master of cinema. He not only conveys the novel's doubts, insecurities, and emotional suffering but does so by transforming internal monologue into visual storytelling. His method is remarkably elegant: he promotes the novel's supporting, almost instrumental character of the chemist, Doctor K., to a embodied second half of unstable protagonist – the psychiatrist, Doctor Hori.

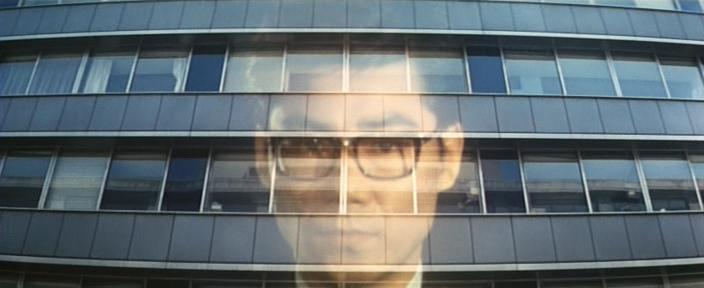

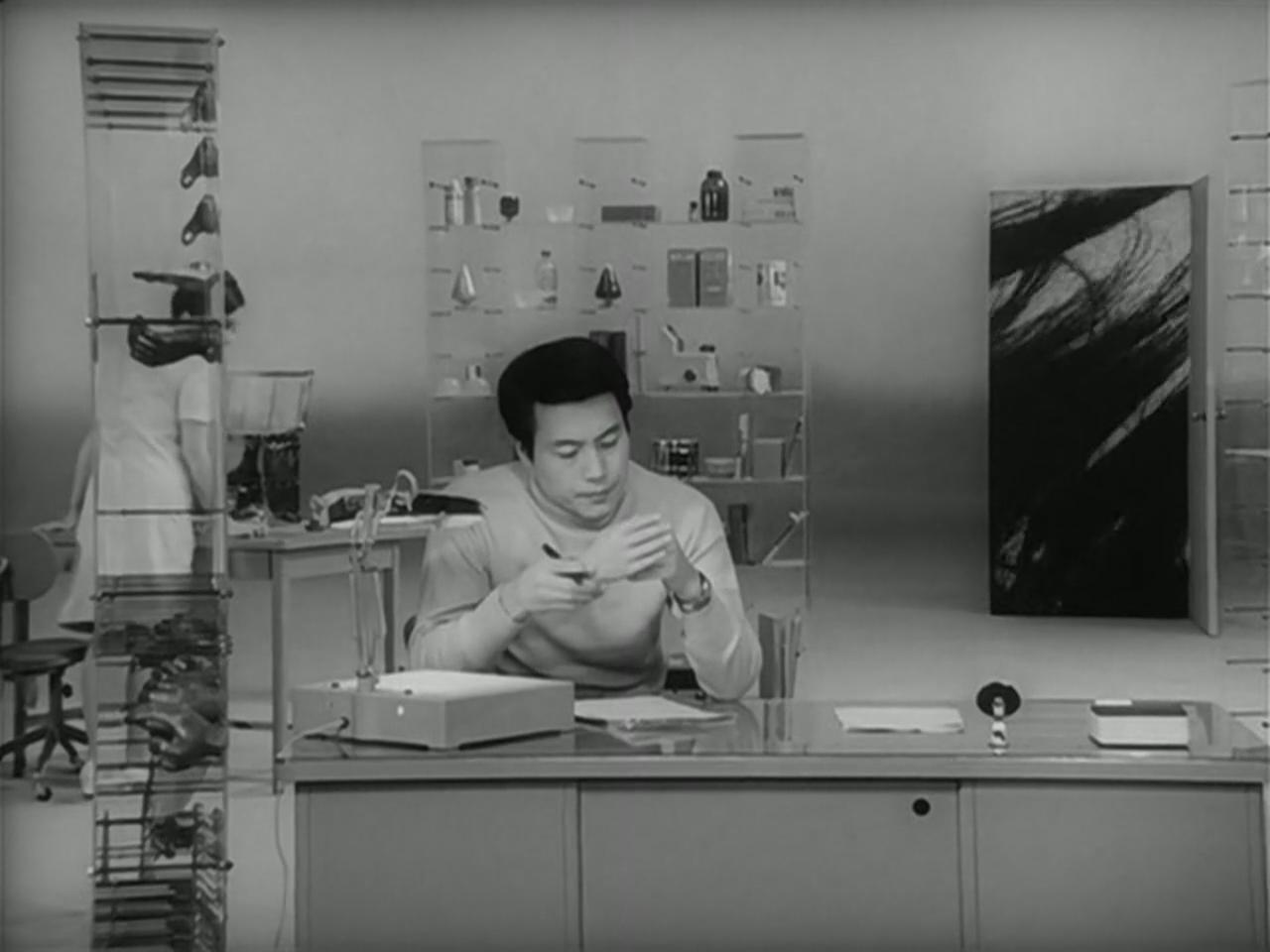

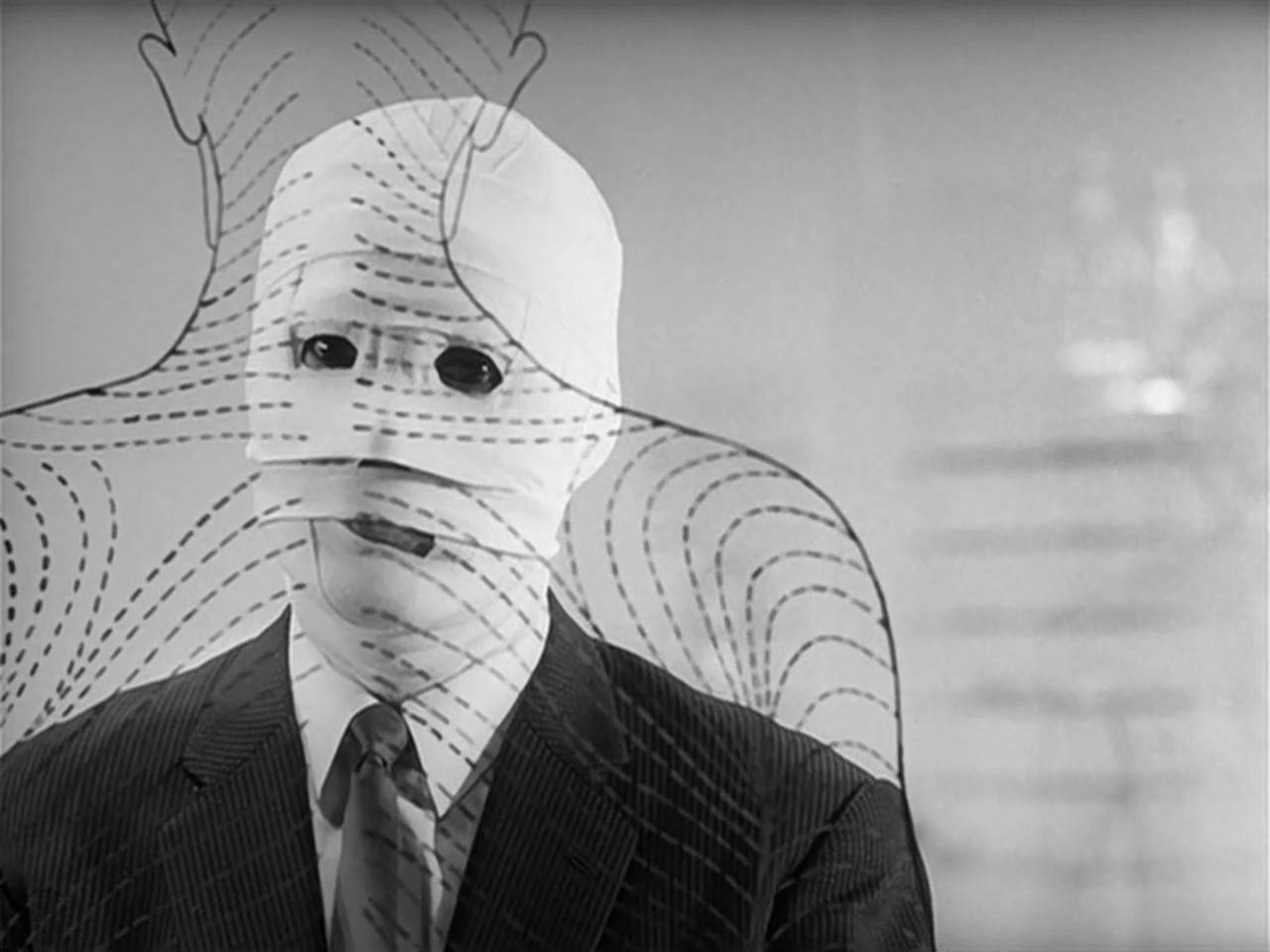

Doctor Hori, played by Mikijiro Hira, is an enigmatic presence. He is first introduced as a voice behind a moving x-ray – a being without an outer shell – yet even in this skeletal form, his presence radiates artificiality, signaled by skull's implanted teeth. He appears to work and perhaps even live in a non-Euclidean limbo – a floating space illuminated by artificial lighting and filled with bizarre objects, strange figures and surreal imagery. We see disembodied prosthetic parts, an obvious metaphor for feeling of detachment, hovering in space and visible from all angles, exposing things not meant to be seen. Diagrams of the human body, such as the Vitruvian Man and Langer's lines, further present the body as a mechanical structure, capable of being deconstructed and re-assembled.

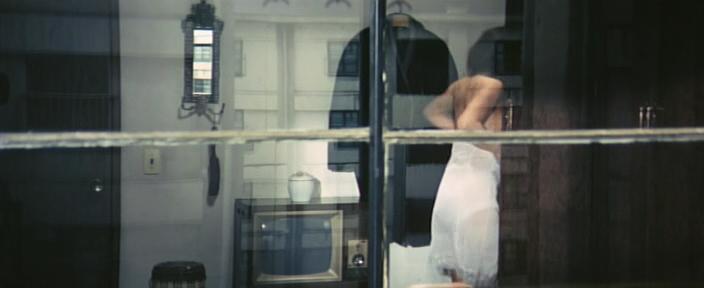

We are soon also introduced to the other inhabitants of this liminal realm: a few assistants, including one young woman who blurs the line between professional nurse and intimate partner; the wife, who drifts from an empty backroom with transparent walls to a surreal flight through the city on a floating bed; and a strange, drug-addicted man, possibly symbolizing a damaged inner ear struggling to maintain balance in this unstable world.

In the novel, Okuyama develops a Jungian interpretation of four basic facial types, outlined in a fictional book Le Visage by Henri Boulan. While this attempt might appear amateurish, it illustrates his grasping for connections in unfamiliar intellectual terrain. In a similar spirit, I found myself using Jungian lens too while interpreting the patient-doctor dynamic. Like the protagonist, I did so in outsider way, limited by memories of two Carl Jung works read some years ago. I believe the accident resulted in a serious hit to Okuyama's consciousness. Not only is his Persona was shattered, his image in eyes of others and ability to merge seamlessly with society, but his Ego, the inner awareness of himself, is in distress too. This collapse of the "I" leads to a descent into the unconscious limbo, where his Shadow gains power and the Complex emerges – incarnated in the figure of Hori.

... The psyche is not a homogeneous structure but apparently consists of hereditary units only loosely bound together, and therefore it shows a very marked tendency to split into parts. The tendency to change is conditioned by influences coming both from within and from without. Functionally speaking, these tendencies are closely related to one another.

Let us turn first to the question of the psyche's tendency to split. Although this peculiarity is most clearly observable in psychopathology, fundamentally it is a normal phenomenon, which can be recognized with/ the greatest ease in the projections made by the primitive psyche. The tendency to split means that parts of the psyche detach themselves from consciousness to such an extent that they not only appear foreign but lead an autonomous life of their own. It need not be a question of hysterical multiple personality, or schizophrenic alterations of personality, but merely of so-called "complexes" that come entirely within the scope of the normal. Complexes are psychic fragments which have split off owing to traumatic influences or certain incompatible tendencies. As the association experiments prove, complexes interfere with the intentions of the/will and disturb the conscious performance; they produce disturbances of memory and blockages in the flow of associations; they appear and disappear according to their own laws; they can temporarily obsess consciousness, or influence speech and action in an unconscious way. In a word, complexes behave like independent beings, a fact especially evident in abnormal states of mind.

– Carl Gustav Jung, "Structure & Dynamics of the Psyche" (1916–1952), paragraph 252-253

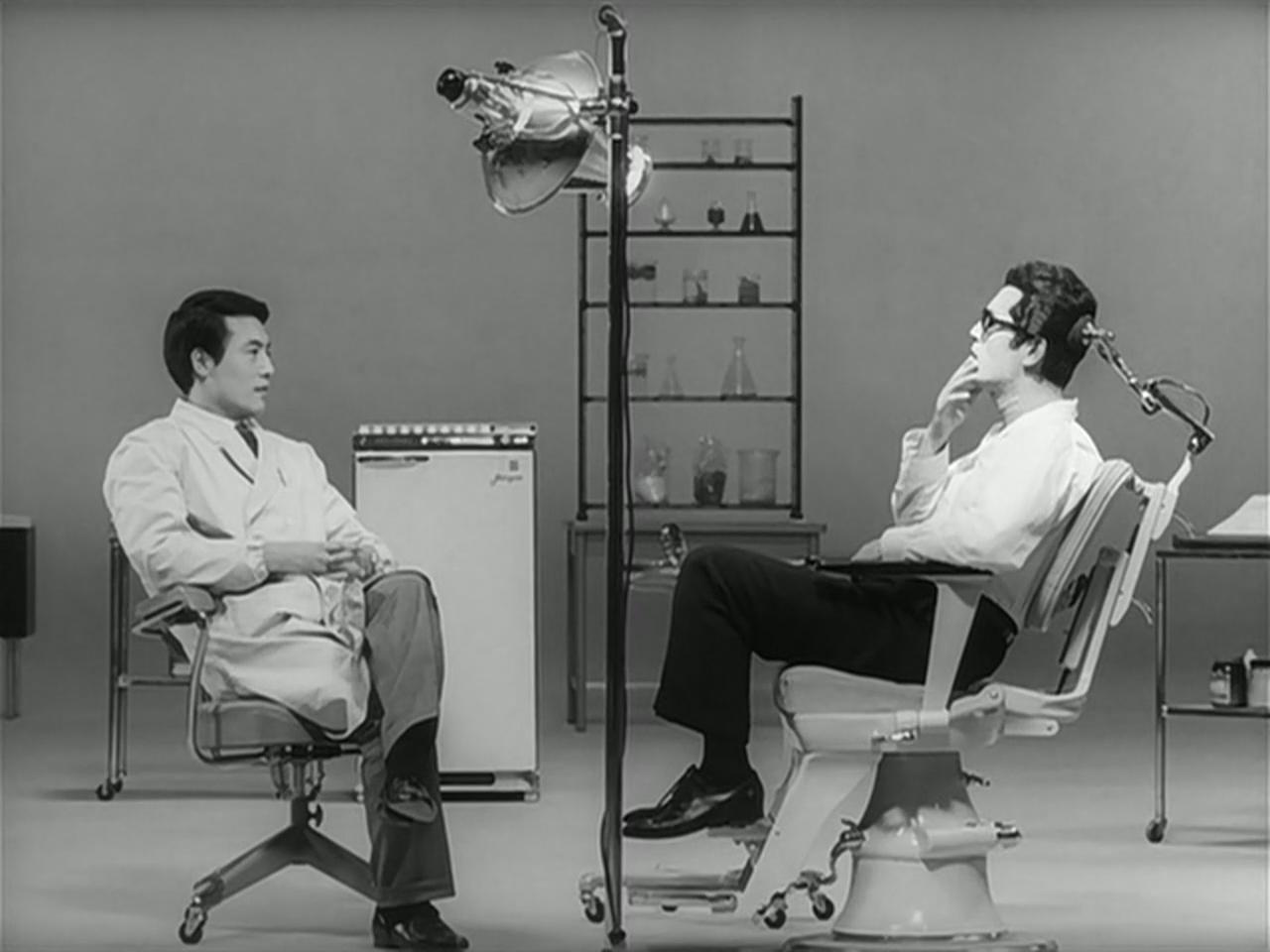

The Complex-Hori exists only in relation to Ego-Okuyama. They are in constant dialogue – not as equals, but more as a wise guide confronting a confused soul. Hori calms Okuyama's anxiety and poses existential questions, like how the creation of a new finger differs from replacing a whole hand, or how artificial teeth differ from decayed natural ones – questions to which Okuyama can give no answer. Their dialogue resembles an inner monologue – a mental weighing of ideas and perspectives. At times, Hori even acts on Okuyama's behalf: giving money to a stranger to "buy" a face or retrieving him from police custody. While maintaining professional distance, Hori discusses intimate aspects of Okuyama's life with remarkable familiarity, as if the two share a common psyche. He does that with delicate touch, never judging nor instigating. They even display similar tics and habits – like ending phrases with a nervous laugh or taking two spoonfuls of sugar.

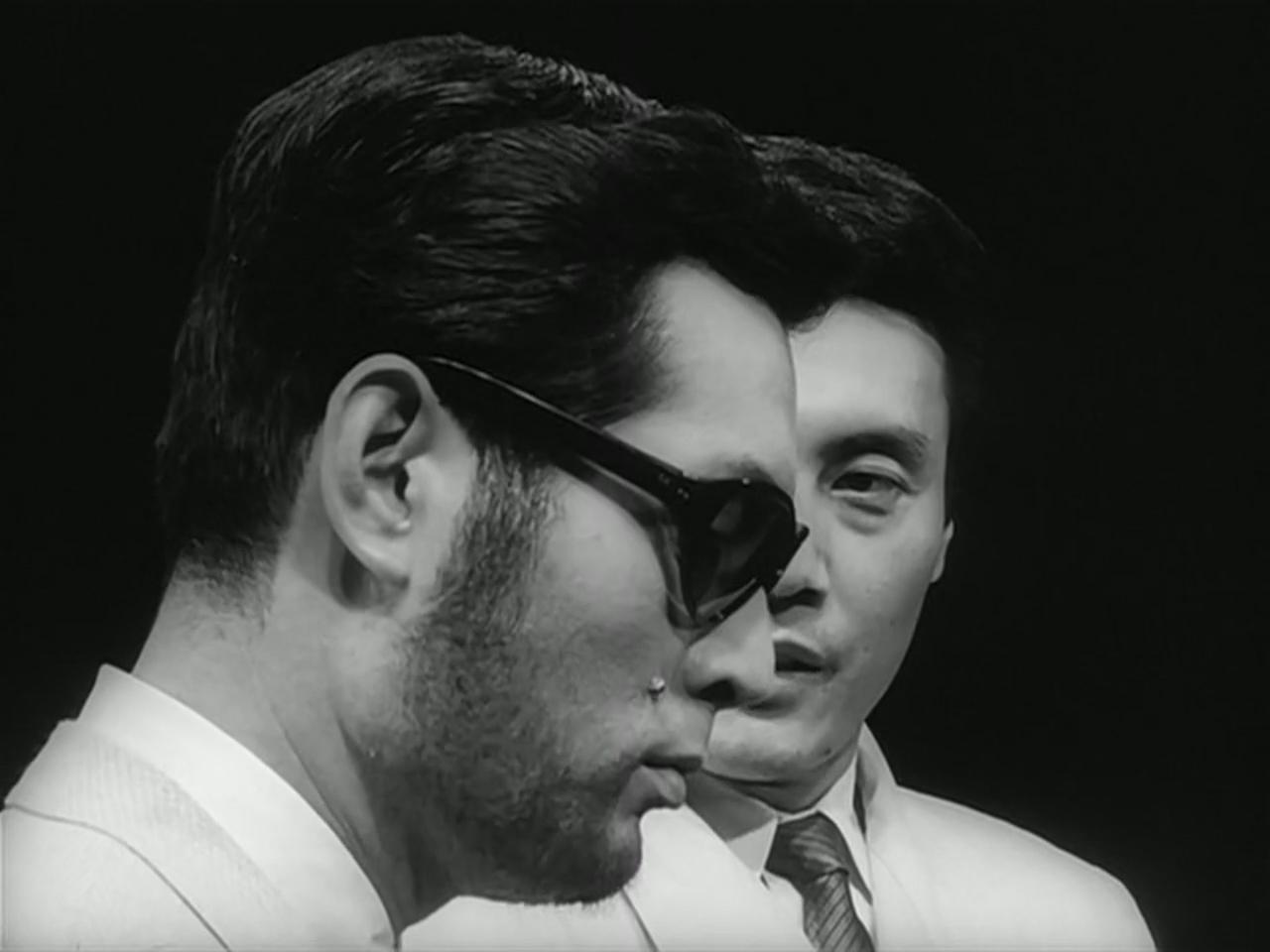

Despite being two halves of a single psyche, they are opposites in their presentation. Hiroshi Segawa's cinematography emphasizes this in nearly every shot featuring both characters. They're often positioned in visual opposition – face-to-face, perpendicular, or top-down – creating a sense of internal conflict. The film's gothic tone and lighting reinforce this tension. Okuyama, with his bandaged, disfigured face, stands in stark contrast to Hori's clean and composed appearance, likewise mirrored in their contrasting outfits. Yet as Okuyama grows accustomed to the Mask, he begins to imitate Hori more closely. He adopts flashy bright clothing, becomes more confident, and even mimics Hori's sinister grin. And the fact that the film can transform the grotesquely scarred Okuyama into Tatsuya Nakadai (one of cinema's most handsome actors) in just a few minutes is not only a textbook case of the "Black Swan to White Swan" transformation but also ironically hilarious.

Still, no matter how much Okuyama tries to emulate Hori, both characters remain more interested in the Mask than in each other. Hori frequently reminds Okuyama that the Mask has a life of its own – "It's not yours to keep" – and insists that he report honestly on what the Mask does. Okuyama's pre-accident collection of masks at his home also suggests a long-standing fascination. As its creator, Hori understands the Mask's power: its ability to transform, to erase identity, and to unleash a kind of freedom that can become nihilistic. Yet he also urges Okuyama to test its limits, teasing him with suggestions like "You'd be safe even with an experienced detective". Okuyama falls into these traps, being wounded by ability of less sensitive to social cues mentally challenged girl to see through his disguise.

After failing to deceive his wife, Okuyama's Ego collapses completely, and he becomes the Mask. He unleashes his Shadow further, moving from emotional abuse of women to outright sexual assault. In a striking stop-motion scene, Okuyama hears someone other than himself mention Hori for the first time. At that moment, he allows Hori to take over again. Later, encountering a crowd of masked people in the street, Hori, horrified, demands that Okuyama fulfill his promise to return the Mask. But Okuyama, now indifferent and detached, refuses. Once a parody of H. G. Wells's The Invisible Man, Okuyama becomes truly invisible in a world saturated with masks. Realizing this, Hori declares that Okuyama – now the Mask – is finally free, rendering Hori's own role obsolete.

There's much more to say about The Face of Another. Like Abe and Teshigahara's earlier collaborations, the film carries political undertones. The subplot involving a girl scarred by the atomic bomb not only offers a parallel path for trauma to reveal itself, but also critiques society's hypocrisy toward innocent victims. Meanwhile, scenes set in a München bar – with Japanese and presumably German crowd – suggest reconciliation and a willingness to move forward. However, as with Pitfall, these themes, though still relevant in their essence, feel buried in their era and have since been portrayed more effectively elsewhere.

Where The Face of Another remains perpetually relevant is in its portrayal of the interplay between individual traits – like the conscious mind and the personal unconscious – and the broader social fabric of the collective unconscious.

Man Without a Map

The Man Without a Map was released in 1968, once again featuring a screenplay adapted by Abe himself, based on his 1967 novel The Ruined Map. It follows an unnamed detective, played by Shintaro Katsu, who is hired by a woman to search for her missing husband. I haven't read the novel, but based on descriptions, I can't shake the feeling of a joke in different naming of the film and the book. In the novel, the wife gives the detective some kind of map that turns out to be useless ("ruined"), but in a film it is changed to a classic noir accessory of two matchboxes, rendering the detective to be literally "the man without a map".

The first thing that catches the eye is the introduction of color, which was absent from the previous collaborations between Abe and Teshigahara. This marks new territory for Teshigahara in feature filmmaking, apart from his work in documentaries. One might expect this new artistic dimension to elevate his already masterful visual storytelling to a new level. But in practice, it feels disappointing – underutilized and ultimately wasted. The world depicted paradoxically feels more muted and depressive than his earlier black-and-white works. The palette looks deliberately washed out, possibly to make bright accents stand out. But those accents end up looking disjointed and out of place. One notable exception are several inverted color sequences near the film's final moments. It's visually striking and complements the experimental tone of Teshigahara's style, but these moments are more like a few bright spots in an otherwise bleak landscape.

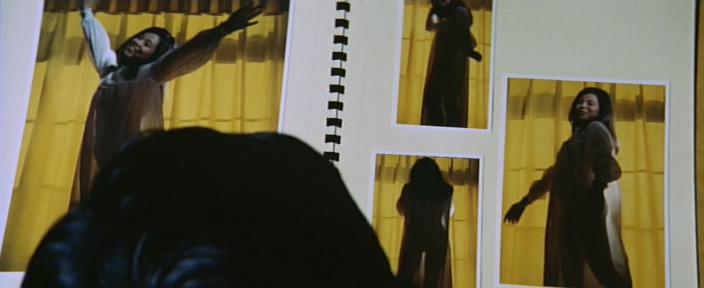

The color-coded accents might serve as visual cues to emphasize objects or ideas of symbolic importance. Red is the most prominent, possibly signaling danger. The most effective use I recall is a scene in which the detective crosses the street as three bright red cars zoom past him – foreshadowing the brutal beating he'll suffer at the bar on the other side. Characters are too color-coded. The wife's brother, who causes tension and trouble in the film's first half, wears aforementioned red, which is an appropriate choice given his role as a pimp. The wife lives in an apartment decorated with yellow curtains and matching flowers, possibly suggesting deception. Later she puts on a ritual black robe for a funeral, finally changing to mystic purple as she moves on from her missing husband to a new lover. The detective's own life is associated with green, whether in the dreamlike image of a young woman in a green skirt or a scene in what appears to be a dress store. This use of color sometimes feels too overt and sometimes too cryptic. There is clearly a pattern, but its coherence is questionable. And more often than not, these bright colors are just distractions on an already busy screen.

Speaking of busy screen, there's a lot going on. Akira Uehara serves as the cinematographer here, replacing Hiroshi Segawa, who shot all previous feature films by this director-writer duo. This change produces a noticeable shift in style. Segawa's camera work was often static, minimal, and symmetrical. In contrast, Uehara's approach is more active, capturing a chaotic and seemingly random world. Close-ups remain, but they're often obscured by foreground elements – objects, curtains, reflections – that partially conceal the characters' actions and emotions. And change from 4:3 ratio to ultra wide 22:9 further compresses the space, making whole experience more claustrophobic.

The characters themselves often feel like accidental participants in the frame. They rarely appear centered, and at most, they occupy a third of the screen. This is heightened by the use of depth-compressing lenses in closed rooms, making figures appear dwarfed by their surroundings, and wide-angle lenses in open spaces to achieve the same effect. The result seems intentional: a world where the environment overshadows the individuals within it. It's a fitting visual strategy for what is, at its core, an anti-detective story. The protagonist not only fails to solve the mystery but may be doomed to fail from the start. Even if the execution isn't flawless, the attempt to enrich the visual language deserves respect.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the narrative. The main character is largely unremarkable – a generic template bearing the usual noir traits: a shady past, personal vices, moral ambiguity and not much more. The supporting characters are even less developed. The cryptic nature of noir doesn't justify how underwritten they are; their motivations are often absent where they should be most apparent. By the end, we know more about the MacGuffin than we do about the people chasing it. There are recurring symbols, such as a maneki-neko with its left paw raised – appearing in both the missing man's and his client's offices – but their significance remains undecodable for me. As for thematic depth, beyond the recurring focus on social alienation, which is typical for both Abe and Teshigahara, little else stands out. This aspect of the film left me disappointed.

In the end, the whole film feels like it's building toward a "Forget it, Jake. It's Chinatown" moment – but that moment never comes.